We often hear about a speaker’s throw, especially in the low frequencies, with terms like “long-throw subwoofer,” for example.

The terms “throw” or “projection” refers to the distance sound can travel while remaining “sufficiently” loud—essentially, how far a speaker can be heard. Talking about a long-throw speaker suggests that some speakers have the ability to project sound further than others. But is that really the case?

To understand this correctly, it is necessary to take a detour through some acoustic principles, particularly different types of sources and the concepts of near-field and far-field.

Simple Sound Source

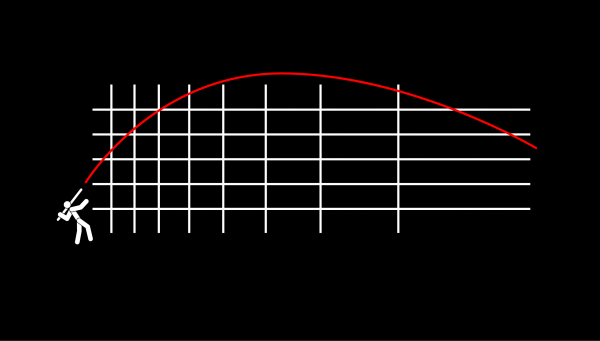

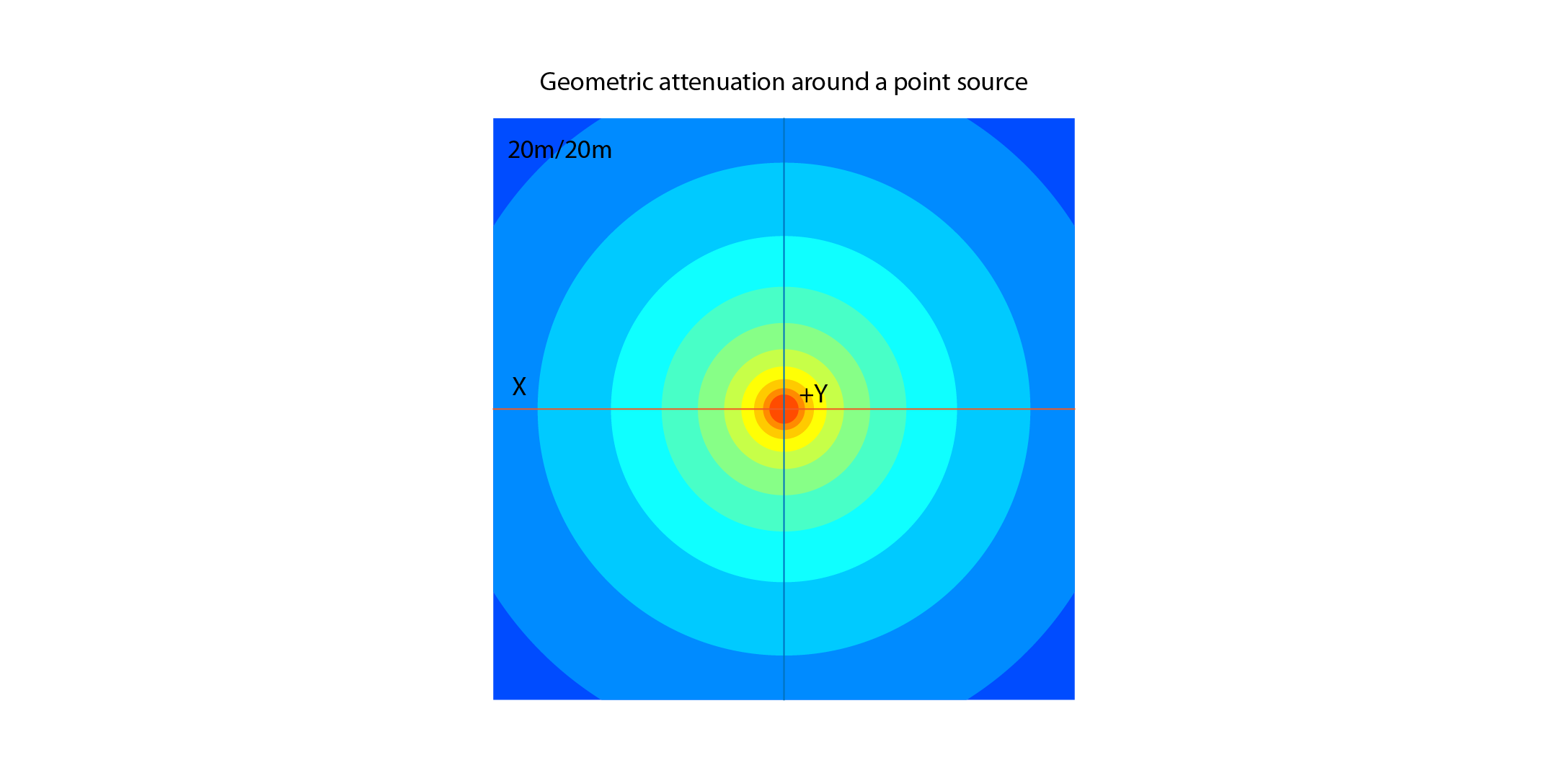

A monopole point source is the simplest model of an acoustic source, generating an omnidirectional wave (meaning the wave propagates equally in all directions, so the sound level is the same everywhere around the source for a given distance). The intensity at a distance r is given by: I = P / (4πr²) where P is the acoustic power emitted by the source. We can notice the 1 / (4πr²) term, which means that every time the distance is doubled, the surface area of the sphere representing the wavefront is multiplied by four. In terms of sound level, this translates to a 6 dB drop for each doubling of distance—this is known as geometric attenuation, as opposed to absorption mechanisms that come into play during propagation (such as imperfect adiabatic processes, friction, etc.), where acoustic energy is transformed into heat.

Near-Field vs. Far-Field

This attenuation law applies to all sources, provided we are in the far-field of the speaker—where pressure and velocity of the wave are in phase. In the near-field, things are a bit more complex. The boundary between near-field and far-field depends on the frequency and the size of the source: the larger the source (for a given frequency), the further this boundary extends from the source.

Speaker Directivity

A low-frequency speaker (subwoofer) can be considered a monopole point source due to the relationship between its size and the wavelength of the generated sound waves, making it omnidirectional.

Conversely, a tweeter (high-frequency speaker) tends to emit sound only within a cone, with little energy outside this cone. This is also due to the ratio between the short wavelengths of high frequencies and the size of the speaker.

It is also possible, for example, through the use of horns, to modify a speaker’s directivity so that it radiates energy only in a specific area. This alters the sound level between the speaker’s axis and its sides or rear.

However, this does not change the geometric attenuation rule—once in the far-field, the sound level will still decrease by 6 dB per doubling of distance, regardless of whether the speaker is omnidirectional (like a subwoofer) or highly directive, and regardless of its enclosure type (direct, horn-loaded, or else).

To verify this, one only needs to measure different speaker types and plot their attenuation curves.

Counterexample: The Line Array

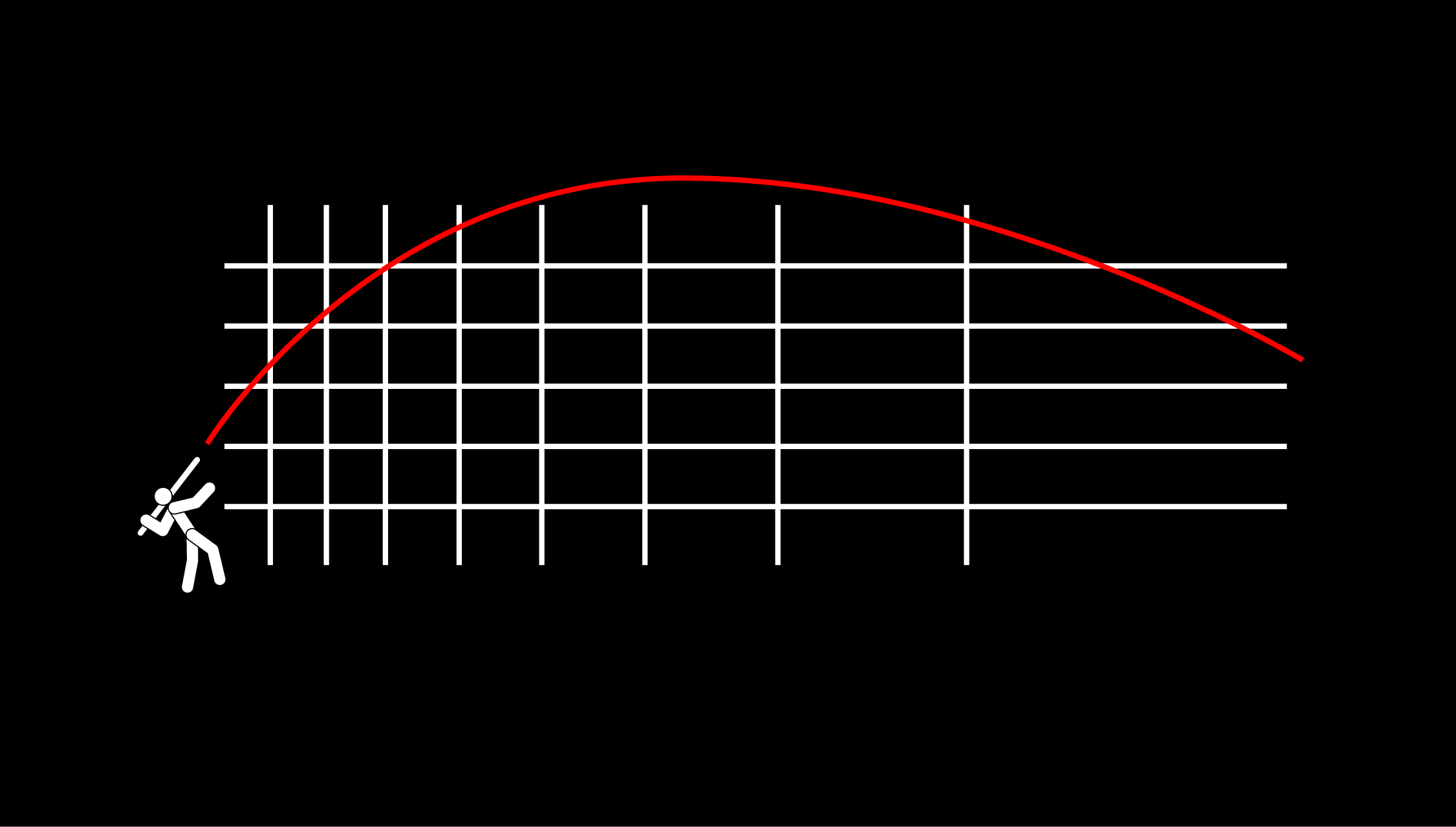

Line array speakers have the particularity of generating sound waves that decay by only 3 dB per doubling of distance in their near-field. By following certain design and implementation principles—known as the WST (Wavefront Sculpture Technology) law—the use of multiple speakers arranged in a line (within specific limits) allows the line array to have a weaker decay than a point source. This effect is known as a cylindrical wavefront (similar to the noise generated by a busy road).

However, beyond a certain distance, the system returns to the general 6 dB rule, producing a spherical wave. This distance depends on the length of the line and the frequency of the wave and is calculated using the formula: D ≈ 1.57 × L² / λ

Note: A single line-array speaker behaves like a point source—it is only by combining multiple sources that the above principle applies.

Conclusion

A standard sound system, which can largely be modeled as a point source, generates a wave that decays at -6 dB per doubling of distance in the far-field, regardless of its directivity or enclosure type.

The only way to maintain a high sound level at long distances—whether the source is omnidirectional or not—is to have a high sound level near the speaker, regardless of the acoustic load used (with the notable exception of line-source systems).

However, a directive speaker can send energy over the heads of the audience and reach distant points without producing excessive sound levels nearby and outside its axis. This might explain why some people talk about “long-throw” speakers. But this does not make any difference to the 6 dB per doubling of distance rule.

Final Thoughts

The term “long-throw speaker” is a misleading expression that does not align with acoustic principles. It is more accurate to speak of directive speakers or speakers capable of generating high sound pressure levels, depending on the context.

To maintain a homogeneous sound level (i.e., a moderate difference in level between the first and last rows of the audience) in large spaces using point-source speakers, several solutions exist:

• Flying speaker systems

• Using delay speakers

• Employing directive speakers, as discussed

For More Information on Directivity and Range:

Acous'tips cardioïd >>

More infos >>